The Siege of Port-au-Prince: Echoes of History and a Cry for Peace

“The thought of such malevolent forces occupying a place steeped in history and learning was profoundly disturbing.”

For some time now, the gates of Port-au-Prince have been breached by what many would call barbarians. This phenomenon is not unprecedented in Haitian history; rural armies have often marched on the capital to dethrone a president. In the past, such upheavals were swift, with leaders paying dearly, though sparing the city’s inhabitants. However, the current siege paints a different picture: the entire city is held hostage by frenzied gangs, leaving behind a swath of destruction—ransacked homes, rampaging crowds, and the flames of anarchy.

This resurgence of the age-old mantra, “Koupé tèt, boulé Kay” (Chop heads, burn down houses), is a grim reminder of a tradition that refuses to fade. It echoes the words of Attila the Hun: “Where I have passed, the grass will never grow again.” Such is the legacy these marauding bands seek to imprint on the streets of Port-au-Prince.

These entities, colloquially termed ‘gangs,’ are a curse upon our society, akin to a terror group devoid of ideology and religious motives. Their barbaric acts are designed to instill fear, to paralyze the populace with shock and despair, indiscriminately targeting all in their path.

According to the latest data from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the exodus has begun, with over 100,000 residents fleeing the city, a testament to the efficacy of terror and those financing the terror!

Amidst this chaos, one becomes numb, desensitized to the relentless barrage of grim news. The daily influx of messages becomes a blur, yet one particular WhatsApp notification pierced through the fog of despondency. It was the news that an anonymous gang had seized control of my alma mater, Saint-Louis de Gonzague. The thought of such malevolent forces occupying a place steeped in history and learning was profoundly disturbing. The school, long perceived as a bastion of the elite, has stood as a prestigious educational institution since the arrival of Les Frères de l’Instruction Chrétienne in Haiti in 1865. The original rue du Centre campus, inaugurated in 1890, is among the few centenarian institutions in the country. Despite its flaws and a history of favoritism, Saint-Louis de Gonzague has been instrumental in educating generations of Haitians.

The legacy of Saint Louis de Gonzague is not merely etched in the annals of Haitian education; it is woven into the fabric of my family’s history. My father, an alumnus from the late 1920s and ’30s, held his education in such high regard that he ensured his sons would walk the same hallowed halls. The comprehensive curriculum of Saint Louis provided him with a foundation that propelled him to university and a successful career as a civil engineer, a testament to the robust educational system of Haiti in that era.

My own tenure at Saint Louis spanned from 1961 to 1966, a period marked by the iron-fisted rule of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier. It was a time when allegiance to the state was not just expected but enforced. Each morning at 8:00 AM, we, the students, would stand to recite the oath of fidelity to the Haitian flag, which, under Papa Doc’s regime, bore the colors red and black, a stark departure from the traditional red and blue. In 1964, the same year Duvalier declared himself president for life, he altered the flag’s hues, a move some historians interpret as an assertion of his “Noirist” ideology. This symbolic act was perhaps a rebuttal to the narrative that Haiti’s independence was secured through the unity of mulattoes and blacks, steering the story towards an exclusively black victory.

Amidst these tumultuous times, Saint Louis de Gonzague stood as a beacon of learning, albeit under the shadow of dictatorship. Les Frères de l’Instruction Chrétienne, known to us simply as Les Frères (The Brothers), had little choice but to adhere to Duvalier’s mandates. Noncompliance was not an option; defiance would have meant expulsion from the country.

Morning Rituals and the Shadow of Doctrine

The expansive schoolyards of Saint Louis de Gonzague were more than just playgrounds; they were the staging grounds for a daily ritual that would begin at the crack of dawn. The atmosphere was reminiscent of a military boot camp, an intimidating presence that greeted every student. Among the ranks of Les Frères were numerous Bretons and Canadians, who would meticulously organize us into formations to recite the oath of fidelity, a solemn pledge to the nation and its guardianship.

The words of the oath were a tribute to the valor of Haiti’s martyrs, immortalized in battles across the land:

“I swear to God and to the nation to be its intractable and fierce guardian.

Let it now float in the blue to remind all Haitians the prowess of our sublime martyrs

who have been immortalized, under the cannonballs and shrapnel,

on the Butte Charrier, in Vertières, in Crete à Pierrot to create a homeland for us

where the Haitian Negro truly feels sovereign and free.”

This ritual, with its stark gesture akin to that of the Nazis, was a daily fixture. We would raise our right arms in allegiance to the flag, a motion so ingrained that it became second nature, resurfacing even in the most mundane moments of daily life. To this day when I shower, I often find myself raising my arm and giving it a good Je jure (I swear). The phrase “Je jure” (I swear) became an echo of the past, a muscle memory that lingered long after the school days had passed.

The origins of this practice were shrouded in mystery, but it was later revealed that a Nazi fugitive had found refuge in Haiti, contributing to the training of François Duvalier’s infamous Tonton Macoutes. Unbeknownst to us then, we were being molded, indoctrinated to become “zombies”, obedient subjects of Papa Doc’s regime, a chilling realization that casts a shadow over those formative years.

A Formidable Introduction: The Dichotomy of Discipline at Saint Louis de Gonzague

“The Frères were infamous for their endorsement of corporal punishment, a practice reluctantly accepted by some parents as a necessary evil in the pursuit of education.”

My inaugural year at Saint Louis de Gonzague was nothing short of daunting. As a six-year-old, far from the comforts of home for the first time, fate dealt me into the hands of the notorious Frère Clair. The school’s entry level, 12ème, was bifurcated into Class A and Class B. Class A was under the stern watch of Frère Clair, a man whose demeanor was as unyielding as iron. In stark contrast, Class B was shepherded by the more compassionate Frère Tarcicio.

The year was 1961, and my initiation into Saint Louis was akin to being cast into a fiery den.

Frère Clair was a compact man, quick to flush with impatience, a veritable volcano in human form, ever on the brink of eruption. His presence alone was enough to instill a perpetual state of alertness in his students.

The Frères were infamous for their endorsement of corporal punishment, a practice reluctantly accepted by some parents as a necessary evil in the pursuit of education. My mother, however, staunchly opposed such severe methods. She twice confronted “Le Frère Supérieur”, advocating against the double dose of strictness that my father already imposed.

The disciplinary arsenal of the Frères was extensive, designed to instill their educational ethos by any means necessary. One such method was ‘Au Piquet,’ where a student would be led by the earlobe to stand, facing a white column for the entirety of the class, forbidden to let their gaze wander.

Frère Ernest, affectionately known as Tiko, was a maestro of this particular punishment. Rumor has it he’s still among us, a nonagenarian by now.

Frère Clair wielded the longest bamboo stick in the nation, capable of reaching from the blackboard to the front row with a single, swift extension. Humiliation was another tool in their pedagogical kit. A mistake at the blackboard could lead to a barrage of insults, a public shaming that served more to erode than to build a student’s confidence.

Among the Frères was Cécilius, whom we dubbed ‘Kaka Doré’ for his blondish hair. He taught us General History, and during exams, he would pace the room before taking his place on the platform, surveying the sea of anxious students.

The phrase “Messieurs, vous avez juste quelques poussières de secondes!” (Gentlemen, you have just a few dust of seconds!) still echoes in my mind, a stark reminder of the psychological warfare waged within the classroom walls. Frère Cécilius, known to us as Kaka Doré, would utter these words with a sadistic glee, his hands caressing each other in anticipation of the panic to ensue. The moment his hands clapped, a frenzy of pens and pencils would dance across the pages, a futile race against the clock.

My classmates, Reimbold, Fouchard, Soukar, Kénol, Rigaud, Fadoul and I were comrades in this academic battleground, united in our struggle against the merciless tick of the clock.

“We devised clever schemes to play tricks on the Frères, driven by a need to even the score against their stern demeanor.”

Transitioning to 11ème marked the end of an era of terror and the beginning of a more humane chapter. Frère Alban, a one-armed disciplinarian whose past was shrouded in mystery, took the helm. We speculated about the origins of his missing hand, perhaps a casualty of war. The truth remained elusive, but his presence brought a sense of humanity to the discipline we had come to expect. The truth of the matter is we never knew much or anything at all about the former lives of these men. I suspect some could have been former military.

What we knew for sure was that they had all power over us. Enrolling in Saint Louis was akin to entering a religious military academy, unbeknownst to us. To make matters worse, the absence of girls on the all-boys campus meant that daydreams were a luxury we couldn’t afford. The strict regimen of Saint Louis de Gonzague left no room for escape, it was our Alcatraz, and we were its unwitting inmates.

The Discipline and Decorum of Saint Louis de Gonzague

Frère Alban’s domain was a realm of unwavering discipline. Our mornings were punctuated by a 15-minute pause for Récréation, a brief respite before the midday interlude at noon. The 11ème class, perched upstairs at the far end of the building, overlooked a quaint schoolyard that I really liked. Dominated by a towering Ficus tree, this yard was a sanctuary amidst the rigor of academic life. The Ficus trees, in their majestic stature, adorned the entire campus with much needed shade.

Adjacent to our classroom stood an edifice from the late 19th century, a testament to architectural resilience, having withstood the ravages of the 2010 earthquake. This structure, a steel skeleton interlaced with bricks, faced Rue du Centre and bore witness to the all-girls school Elie Dubois, which recently fell victim to the treachery of the gangs.

Our recreational breaks were orchestrated with military precision, even the visits to the Pissoir (Urinal). It was November 22nd, 1963, when the routine was shattered by news that would echo through history. Frère Alban, with a look of disbelief, conveyed the tragic message: “Kennedy à été assassiné” (Kennedy has been assassinated) to Madame Cameau one of the lay teachers on campus.. The gravity of President Kennedy’s assassination was beyond my youthful comprehension, yet the moment is indelibly linked in my memory to the mundane act of using the urinal, a poignant juxtaposition that underscores my deep-seated connection to Saint Louis de Gonzague.

Frère Alban, a figure of medium stature with bespectacled eyes, was distinguished by the bluish hue of his shaven face. His attire was emblematic of rural France, with sandals and white socks that seemed foreign to Haitian soil. The Frères’ uniform was a long white Soutane (Cassok), reminiscent of a Nehru suit, clasped tightly at the neck and adorned with a sizable black and silver cross, the emblem of their order. Only Frère Louis, who presided over the other 11ème class, deviated from this tradition with a black Soutane.

Childhood Schemes and Schoolyard Dreams

As children, our mischievous minds were always at work, especially during recreation at Saint Louis de Gonzague. We devised clever schemes to play tricks on the Frères, driven by a need to even the score against their stern demeanor. You need to understand that the Frères were just mean! One such plot involved the Soutane and our curiosity about its cleanliness. Our desks, long and shared, featured inkwells for our feather-like pens. During one orchestrated act, a classmate would mark the Frère’s Soutane with ink, setting a clandestine timer on its wear before washing. To undertake this operation we had to be vigilant and discreet as there were a couple of well known traitors amongst us, you know the ones that would run up to the Frère after class and snitch on you! To our astonishment, the Soutane would go unwashed for weeks, confirming rumors about the French aversion to frequent baths.

Despite the religious oversight, Saint Louis had its share of lay teachers. Madame Anthony and Madame Cameau took charge of the 10ème classes, while Madame Lespinasse and Madame Lescouflair presided over the 9ème. These Haitian instructors, clad in tan dresses and adorned with the school insignia, brought a different energy to the classroom. Madame Cameau, my future teacher, was known for her extravagant butterfly glasses which were very much in vogue in the sixties and her collection of pointed shoes. Years later in New York city, we would call shoes like that “Porto Rican fence climbers” or “roach killers”.

Frère Alban, a figure of intrigue, was occasionally spotted during recreation with one of those ladies in what seemed like intimate exchanges behind a courtyard fence. These sightings, reminiscent of the secret liaisons in Billy Paul’s classic song “Me and Mrs. Jones,” added a layer of human complexity to the otherwise austere environment. No question about it, Frère Alban was in my opinion an eager beaver, better yet, he was a one arm bandit!

The midday break unleashed us into the schoolyard, where the Frères distributed footballs from large fishnet bags. We’d eagerly form a “Deux camps” (opposite teams) for a spirited game, a cherished respite from academic rigor. Marbles, too, were a favorite pastime, with each type earning a nickname reflective of its condition or luster. These names, Chenelle for the shiny, Grizon for the worn and Bika for the much larger marble would later find new meaning in our adolescent lexicon, illustrating how the language of the schoolyard can shape our expressions for years to come. Indeed, the schoolyards of the republic are the birthplace of many derogatory words of the creole language!

Lunchbox Chronicles: A Tale of Simplicity and Scrutiny

“At Saint Louis, it wasn’t just the students who engaged in name-calling; some of the Frères participated as well.”

The lunch menu from my childhood home was a humble affair, crafted by a maid with five hungry mouths to feed. My lunchbox would often contain a simple egg or peanut butter & jelly sandwich, sometimes just bread paired with “La Vache qui rit”, a modest cheese not to say the cheapest cheese around! Occasionally, I’d find a spam sandwich nestled within, but the bane of my lunchtime existence was the sardine sandwich, a flavor I’ve since sworn off for life. God, how I hated sardines! To this day I cringe when I see a can of sardines on the shelf of a super market!

Accompanying these mainstays would be a piece of fruit, perhaps a banana, an orange, or a Cachiman (Custars apple) and a thermos brimming with orange juice or sugary Haitian lemonade. In stark contrast, some of my peers flaunted lunchboxes filled with exotic fruits like apples and pears, which were totally foreign to me back then!

In Japan, where I lived years later, I discovered a culture where the visual appeal of a meal was paramount. Japanese mothers would artfully arrange their children’s lunchboxes, turning each meal into a feast for the eyes. This meticulous presentation was a far cry from the hasty assembly of my own lunches, which were more about sustenance than style.

Lunchtime in the schoolyard was also a stage for playful banter and, at times, cruel jokes. The shape of one’s head could become the target of ridicule, with nicknames like “Tèt zo” for the slender, “Tèt Bika” for the round, and the dreaded “Tèt Chaloupe” or “Tèt Cercueil” for those with more pronounced features. These labels, once uttered, had a way of sticking, sometimes for a lifetime. You wanted to avoid these two at all cost!

I’ve come to believe that the seeds of malice are often sown in the schoolyard. At Saint Louis, it wasn’t just the students who engaged in name-calling; some of the Frères participated as well. A tale is told of a dark-skinned student (way before my time) that the Frères had brutally nicknamed “Blackie”, he would grow up to embody the cruelty he once endured, becoming a feared figure within the Haitian army and committed some of the most heinous crimes under Duvalier. His story is a stark reminder of the lasting impact of childhood scorn and the societal acceptance of such inequalities.

In the tumultuous era of the sixties, under Duvalier’s rule, the Haitian regime deftly wielded the race card, a move that reverberated through the nation’s complex post-slavery society. Haiti’s racial dynamics, while echoing other post-colonial societies, stand out with their unique intricacies. For example, it’s considered acceptable for a black Haitian to label a lighter-skinned individual whether white, mulatto, or a grimaud like myself as a “Blan,” (a white person) instantly casting them as an outsider. This label signifies a disconnection from the larger community, a stark reminder that one’s skin color can render them an anomaly amidst the black majority.

My personal journey with racial identity took a turn upon my arrival in the United States. Here, the spectrum of blackness embraced even those of us with lighter skin. The African American community, exhibiting a greater tolerance, might refer to us as “High yellow,” yet we were unequivocally black. The irony was not lost on Haitian mulattoes who, upon setting foot in America, were suddenly confronted with their own blackness a revelation that elicited both shock and laughter.

The racial climate in America was so fraught that African Americans were in dire need of solidarity. Haiti, however, presented a contrasting narrative. Here, a light-skinned black person was often viewed as a foreigner, relegated to the ranks of the mulatto class or whites. I was dubbed “Ti Rouj” (Little red one), and long ago, I ceased the futile endeavor of justifying my blackness in Haiti. Countless times, I’ve been queried about my fluency in Creole, as if my speech betrayed a non-Haitian origin. Street harassment for money became a common occurrence, as if my presence implied an obligation to dispense cash. Nowadays, the aggression is palpable, yet my affinity for walking the streets no matter their state remains undiminished.

In Haiti, accusations of exploiting one’s lighter skin for privilege are not uncommon, a regrettable truth in our society. To illustrate the flip side of this dilemma, imagine being embroiled in a heated dispute, your temper flaring, and in the heat of the moment, you cast the slur “Nèg Nwè” (intensely black) at your adversary. Such is the complexity of racial discourse in Haiti a land where the shades of skin can both unite and divide.

To utter the term “Nèg Nwè” in Haiti is to invoke a legacy of oppression, a stark reminder of the brutal days of French colonial rule and the harrowing history of slavery. This phrase carries a weight that transcends mere words, encapsulating the deep-seated memories of a past that continues to shape the present. It is a term that, in the Haitian context, is arguably harsher than the “N-word” in America, laden with implications of illiteracy and lack of sophistication a label that strips away dignity and denies the prospect of social advancement.

In Haiti, race relations are not a subject of levity but a profound source of societal tension. The 160-year French dominion over the island has left an indelible mark, a legacy of division and struggle that persists to this day.

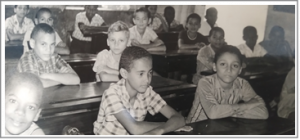

The Frères of Saint Louis de Gonzague, cognizant of the delicate intricacies of race, sought to bridge these divides. They provided an inclusive education to all, regardless of racial background, black, mulatto, or white. The class photograph accompanying this article serves as a testament to their efforts, showcasing a diverse tapestry of students that mirrors the full spectrum of Haitian society. From blacks to whites,

“The Methodist institution, merely a stone’s throw away, became the scene of an assassination attempt that claimed the lives of Jean Claude’s bodyguard and driver, though he and his sister Nicole miraculously survived.”

quarterons to mulattoes, marabous to bruns, grifs to grimauds, the array is as vast as it is vibrant. Indeed, Moreau de Saint Méry, a French colonizer and historian, once identified an astonishing 120 different shades within the colony.

Our shared experiences at the Frères of Saint Louis de Gonzague fostered a camaraderie that, for many of us, blossomed into lifelong friendships. The issue of favoritism at Saint Louis de Gonzague was nuanced, more a whisper than a declaration, yet its presence was undeniable. It wasn’t institutional policy to bestow advantages upon the children of the bourgeoisie over those from humbler beginnings. Rather, it was the individual disposition of each Frère that dictated such biases.

The seasoned Frères, those venerable “dinosaurs,” had a penchant for connecting students to their familial legacies. A surname could evoke memories of a father’s scholarly pursuits, potentially benefiting the son if his progenitor had been exemplary. Under such a Frère’s tutelage, a student with promise could flourish. Conversely, a lackluster performance might elicit a public reprimand, a scathing comparison to a more illustrious father, intended to spur the student to avoid becoming the “family dummy.”

Politics, the bane of Haitian society, infiltrated even the sanctity of education. The Frères, despite their divine calling, were not impervious to its influence. A stark illustration of this was the enrollment of Jean Claude Duvalier following a harrowing ordeal at College Bird on April 26, 1963. The Methodist institution, merely a stone’s throw away from Saint Louis, became the scene of an assassination attempt that claimed the lives of Jean Claude’s bodyguard and driver, though he and his sister Nicole miraculously survived. In the aftermath, a vengeful Papa Doc unleashed a brutal crackdown, targeting innocents in response to the machinations of his former henchman Clement Barbot.

In those days, it was customary for my father to drop us off in school in the morning. He drove this 1957 Chevy Pick up, the vehicle belonged to an American project that he worked for. Our neighbor, Jean Camille, son of the esteemed poet Roussan Camille would hitch a ride with us in the morning. My dad would drop him off in school and I particularly remember how we all loved riding down the Bois Verna road in the back of that pick up truck. Unlike the rest of us, Jean attended College Bird, and on one fateful morning, I remember clearly that Jean’s tardiness had irritated my father. Little did we know that the lateness of my neighbor Jean would shield us from the chaos that unfolded on April 26, 1963. The rapid spread of news, or “Télédiol” as we know it here, prompted my father to keep us home, narrowly evading the violence that erupted at College Bird, where an assassination attempt on Jean Claude Duvalier claimed many innocent lives. The most tragic incident of that ill fated day was the brutal killing of François Benoit’s parents, the torching of their house along with Benoit’s baby boy who was a mere 7 months old! Benoit was then a young decorated army officer who had won a sharp shooting competition in Panama. In the minds of the wicked Duvalier supporters, only a sharp shooter with Benoit’s skills could have staged such a spectacular assassination attempt! My friend Marie Louise Fouchard’s father, an army officer in civilian attire, also fell victim to that tragic day. I owe a debt of gratitude to Jean Camille; his leisurely pace that morning may well have saved our lives when Papa Doc deployed all his ugliness and cruelty!

As a reminder, for those of us today that are nostalgic of the law & order regime that Francois Duvalier imposed on Haiti, please remember as well that his reign was one of sheer terror!

Jean Claude Duvalier’s attendance at Saint Louis de Gonzague

Jean Claude’s arrival at school was always discreet, entering through the back gate on Grand rue. A stylish sky-blue Buick Electra 225 regularly dropped him off. The car would leave and come back to fetch him at the end of the day when school was over. Flanked by two iconic Tonton Macoutes, donning fedoras and dark glasses, they remained vigilant by his side. Such security measures were a stark contrast to the typical parental drop-offs at the main entrance on rue du Centre, a necessity for this high-profile student in the wake of the College Bird incident.

From my classroom doorway, I often observed one of Jean Claude’s guards, statuesque and armed, overseeing the schoolyard. The Frères, bound by circumstance, tolerated their presence, a delicate balance of power and necessity. My memories of Jean Claude paint him as a model student polite, composed, and well-mannered, sharing classes with my elder brother Lionel. When he came to Saint Louis in 1964 I, he must have been 13 going on 14 years old. Jean Claude was an obese young man, he had this rotund shape about him. He had a distinctive gait and was also knock knee which meant that when he walked past you, you could hear the soft rustle of the cloth material between his legs. In those days, Dacron Polyester pants were very much in style. Those polyester-clad Macoutes, no doubt, kept the local Arab cloth merchants prosperous, as the fabric’s popularity soared. Amidst games of marbles beneath the Ficus trees, I remember a classmate saying Here comes Jean Claude! You could hear Chi..Chi..Chi..Chi..Chi in the near distance and you just knew it was Jean Claude approaching. A sound as unmistakable as his presence!

Jean Claude, with his genial disposition, effortlessly found his place among us. His generosity was legendary; during breaks, he was the patron saint of the schoolyard, where Abner, the custodian, ran a makeshift canteen. It was there we indulged in the simple pleasure of “Dous” sandwiches, the sweetness of the treat perfectly complemented by the fizz of a Cola Couronne Champagne. The less fortunate students, known colloquially as “Reskiyè” (Freeloaders), gravitated towards Jean Claude, who never hesitated to share his wealth. Abner, well aware of these usual suspects, turned a blind eye, while his wife’s Comparet (a hard cake like bread), dubbed “Micheline,” became another staple of our school time feasts.

Saint Louis de Gonzague was more than an educational institution; it was a melting pot where we learned about life’s less savory aspects, including the brazenness of those who shamelessly sought advantage. Haiti, as I would come to understand, was a land where such traits were not in short supply.

In the tumultuous landscape of Haitian history, we encounter the son of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, a dictator whose reign was marked by fear and oppression. The Jesuits, expelled from Haiti in 1964, were but the first in a series of expulsions that culminated with the Spiritains of Petit Séminaire Collège St Martial in 1969, accused of collusion with underground political movements. Papa Doc’s reputation was one of a man not to be trifled with, a man who would not tolerate humiliation.

The educators at Saint Louis de Gonzague were acutely aware of the precariousness of their position. Operating a school under the shadow of Duvalier was akin to handling a live grenade. Saint Louis, a bastion of education and profit, would have shuttered its doors had it not been for its financial viability. The prospect of Jean Claude Duvalier, the president’s son, repeating a grade and facing the ignominy of ‘Doubler’ was unthinkable. Such an event would have branded him as intellectually deficient, subjecting him to silent ridicule from his peers. If the rumors held any truth, the decision to avoid this scenario was a prudent one, better to retreat and live to fight another day.

Jean Claude Duvalier’s tenure at Saint Louis de Gonzague is often cited as a glaring example of favoritism, a concession to a ‘Force Majeure’, an irresistible force.

“This era of fervent patriotism and civic virtue predates Haiti’s descent into turmoil.”

The curriculum at Saint Louis was comprehensive, encompassing French grammar, composition, orthography, geography, history, mathematics, science, Latin, catechism, and writing, not to mention ‘Histoire Sainte’. Students were also encouraged to engage in sports, with facilities for volleyball and football, and the school boasted a formidable track and field team. These activities took place at Park Saint Louis, a vast athletic complex owned or leased by the Frères, situated behind the Haitian Army Corps of Engineers in Saint Martin.

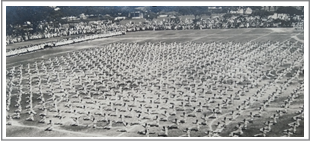

Historically, Haitian schools like Saint Louis de Gonzague played a pivotal role in the patriotic celebrations of May 18th, Haiti’s Flag Day. Students would diligently rehearse choreographed routines in anticipation of performing on the National Palace’s front lawn, under the watchful eye of the president. A family photograph from the 1940s bears witness to the grandeur of these events, a stark contrast to the lackluster performances of modern times.

This era of fervent patriotism and civic virtue predates Haiti’s descent into turmoil. The legendary Haitian storyteller Maurice Sixto with whom I was collaborating on a film project, once told me that his experiences under Duvalier represented the ‘Golden Age of Mediocrity’. Had he witnessed the current state of affairs, one can only speculate on his assessment. It is evident that Haiti has suffered profound losses, plunging headlong into an era of ‘Kokoratisation’, a cultural shift towards embracing ignorance as the norm.

In preparation for the grand display of discipline and unity on Flag Day, the Frères orchestrated a march that would take us through the heart of Port-au-Prince, all the way to the district of St. Martin. This journey was not just a walk; it was a procession that painted a vivid tableau of the city’s diverse social landscape. We, the students, became a living exhibit, threading through neighborhoods that spanned the economic spectrum.

During the era of François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, the city was under an iron grip, “Plume pa gouyé” (Nobody moves), as the saying went. Haiti then was home to a mere 4.5 million souls, a stark contrast to the teeming 12 million of today. Our march began at the main gate on rue du Centre, snaking through the city’s arteries, rue Pavée, Rue des Miracles, rue Bonne Foi, and onto rue des Fronts Forts. We might have veered right, marching past the cathedral on rue Dr. Aubry, and

“With bated breath, we hoped for grades that would spare us from parental chastisement.”

through the expansive neighborhood of Bel Air, before descending into the sprawling district of St. Martin. The procession was a long column of youth, shepherded by a Frère at the helm and another bringing up the rear. Though my recollection of the exact route may falter, the memory of passing the ornate Pharmacie Séjourné, a casualty of the devastating earthquake, remains vivid.

The Frères were our steadfast guides, setting the pace and allowing no deviation from the task at hand. Reflecting on those times, I realize it was more than a march; it was a lesson in resilience and determination. As we ascended into Bel Air, the pace quickened to navigate the hilly terrain that offered a panoramic view of downtown Port-au-Prince and its bustling port. At the heart of Bel Air stood the statue of Madame Colo, an emblematic figure of the neighborhood, immortalized in bronze atop a pedestal. This fountain, dedicated to a woman who spent her life selling spices, was a testament to the spirit of Bel Air.

The streets were alive, teeming with a sea of humanity so dense that no vehicle dared to enter. The name Bel Air, or ‘Fair Breeze,’ might evoke images of tranquility and ostentatious homes, but this was not the Bel Air of Los Angeles, California where, my friend Richard Casseus and I once found ourselves out of place! Our smoky 1968 Dodge Dart and our extravagant Afros were a stark contrast to the opulent surroundings. We were kindly escorted out of that Bel Air! The Haitian Bel Air of the mid-sixties on the other was a bastion of the working class, a safe haven for artisans, school teachers, and the creators of the finest voodoo flags. Once a prestigious district at the turn of the last century, Bel Air has since transformed, bearing the scars of time and turmoil, a stark reminder of the impermanence of status and the relentless march of change.

My academic journey at Saint Louis was far from stellar; I was the quintessential average student, skirting the precipice of failure with just enough effort to pass. The Frères, with their daunting presence, cast a long shadow over my school days, turning the classrooms into arenas of silent prayers for invisibility. The mere thought of being called upon was enough to send shivers down my spine, as any misstep would invite a public reprimand, a humiliation I was fortunate to avoid.

Despite the fear, I persevered, driven by a determination not to wear the metaphorical ‘dunce cap’ of Bourdon, my neighborhood. The specter of ‘Doubler’ loomed large, but through diligence in my studies and homework, I managed to evade it, much to my parents’s relief.

Among my peers, there was a guy whose last name was Adam, his first name escapes me, a prodigy who consistently ranked at the top of our class. His quiet demeanor belied the academic prowess that saw him effortlessly outpace the rest of us. Living just a stone’s throw from the school gates, Adam’s journey was as short as the time it took for him to claim the number one spot each month.

The arrival of the Carnet Scolaire on the fourth Sunday of every month was a moment of reckoning. With bated breath, we hoped for grades that would spare us from parental chastisement. The report card listed fifteen subjects, though only five bore the weight of our academic fate. A score of 10 out of 20 was the threshold for success, and I hovered modestly above it, finding solace in my homework where I fared better.

“In my youth, I harbored a rebellious spirit, questioning the necessity of confession.”

Looking back, I harbored a fondness for most subjects, with the notable exception of mathematics. Arithmetic and algebra were my nemeses, none of it registered! Leaving Haiti after the 8eme was a timely escape from the clutches of trigonometry that lay in wait.

The 8eme class was overseen by a Frère whose name is lost to time, but whose disciplinary tool, a stick he dubbed ‘Pepsi,’ is etched in memory. The ritual was simple yet dreaded: an outstretched arm, an open palm, and a series of swift, stinging strikes. It hurt like hell! Most students would stick their arm out to quickly retrieve it, this game would go on for a few minutes but this Frère always gained the upper hand with his cruel punishment. The only student who stood up to this beast was Hugues Paris a french student who looked at the Frère as if to tell him “Is that all you got”. Most students would would scream in pain or cry but not Hugues!

It was a painful lesson in discipline, one that left a lasting impression far beyond the classroom walls.

The sanctity of Sunday mass at Saint Louis was enshrined in the school’s regulations, a mandate that held the threat of expulsion over any who dared to defy it. The “Extrait du règlement” was clear: attendance was not merely encouraged; it was compulsory. The uniform of white was a symbol of purity, a testament to the religious rigor that permeated every facet of the curriculum. Communion was not a choice but an obligation, leaving no room for personal interpretation or dissent.

In my youth, I harbored a rebellious spirit, questioning the necessity of confession. To feel the need to confess is to clear your conscious of wrongdoings but why should one confess if one hasn’t sinned? This paradox led me to fabricate transgressions, a practice that ironically cast me into the role of a sinner in pursuit of absolution. It was a moral quandary that I discussed with my friend Jean Fabius, who shared his own experiences of navigating the confessional’s expectations with innocuous admissions of lying and cursing, mere venial sins in the eyes of the expectant priest.

The chapel of Saint Louis stands as a testament to architectural ingenuity and historical significance. Constructed from prefabricated steel, it arrived from France in pieces, only to be assembled on Haitian soil in 1896. This centennial structure, a product of Frère Odil’s vision and French craftsmanship, underwent a solitary restoration in 1968. Its creation was inspired by the Paris Expo of 1889, which heralded steel as the material of the future, much like the Eiffel Tower before it. Haiti, along with other Caribbean nations, embraced this trend, leading to the rise of fireproof structures akin to Port-au-Prince’s Iron Market. The devastating fire of 1896 in Jacmel prompted traders to seek these durable edifices, a choice that would shape the architectural landscape for years to come.

The Maison Boucard stands as a magnificent relic of Jacmel’s past, its ornate and grandiose facade defying the passage of time. Similarly, the chapel at the Archevéché (Archdiocese) of Port-au-Prince, a smaller counterpart to Saint Louis’s own, has proven its resilience, surviving the earthquake that brought modern structures to their knees.

Sunday services at Saint Louis were more than a religious observance; they were a communal event where parents and educators came together, united in their commitment to the student’s growth. Before the service, everybody would congregate in front of the chapel looking elegant, respectable and proud and we students didn’t disappoint either in our sparkling white attire. It was quite an affair on “rue du Centre” with cars parked on both sides of the street. The chapel, a beacon of elegance, welcomed all with its stained glass windows that narrated the path of Jesus to crucifixion. I am not much on churches but I have to say that I truly liked that chapel. The central aisle, adorned with exquisite tiles, led the faithful to the altar.

The chapel also served as a sanctuary for confession and prayer. On Sundays students were seated in the first 10 rows for the service while the back benches were reserved for parents and family members. It was a clear divide which reminded us that the service was done for the purposes of the students. Every Sunday the Frères would select a star student to read a passage of the scriptures, Michel Soukar, a paragon among us, often graced the lectern.

Although church service on Sundays was a stiff affair, we managed to always find a way to crack a few jokes and giggle a bit. One Sunday after communion, I sat next to my friend Jean Chenet, I liked him a lot because he was a whirlwind of energy and humor, and he was a fast talker! We called him “Ti Jean”. We did our 8eme classe together and we both left Haiti in 1966. He once told me a joke about a guy who was queuing up for communion and the priest or the altar boy had accidentally dropped a piece of rubber in the paten. So when it was the guy’s turn to receive communion, he had his mouth wide opened and the priest told him “Le corps du Christ” (The body of Christ) and then inserted that piece of rubber in his mouth. The poor guy turned around and walked back to his seat and all along he was chewing on that piece of rubber thinking it was an “Hostie” (Host). So finally the guy still chewing the rubber turned to someone else next to him and asked him: “Say, what is the host made of?” To which the other person reply: “Why it’s the body of christ, don’t you know that?” The rubber guy by now looking real vexed, turned around to the other person and told him: “Looks like I got a testicle today!”

Well with jokes like that, clearly some of us had zero interest in church service. I stopped going to church at the age of 15 or 16 in New York much to my mother’s dismay. As for Ti Jean, life has a way of weaving paths back together, as I later reconnected with him in the bustling boroughs of Queens in New York. He lived in Lefrak City walking distance from my neighborhood Corona. Ti Jean became a successful hair stylist and a sharp dresser!

First communion at Saint Louis

The rite of First Communion at Saint Louis was an elaborate affair, a milestone in the spiritual journey of a young student. The Frères dedicated months to our catechetical instruction, ensuring we were well-versed in prayers and confessions, ready to embrace the divine. This spiritual molding by the Frères was complemented by the practical preparations undertaken by our parents.

For me, the lead-up to this sacred event was orchestrated solely by my mother, as my father had then found work in the Congo. Our family’s Vauxhall station wagon, an English import popular in the ‘60s, became the chariot for these preparations. Despite my mother’s aversion to driving and her nagging insistence on keeping her foot on the clutch, my mother took charge, a testament to her hands-on approach to life.

The initial step was a visit to Albert Goldman’s barbershop, a Jewish establishment known for its spinning barber pole, a beacon of tradition and commerce. There, I received the quintessential “Tèt Kalé Bobis” haircut, a style I protested with fervor but to no avail. The close shave, mandated by the Frères and executed by Albert Goldman, was a symbolic act of purification, though it also made me the target of playful jests from my peers.

In hindsight, this experience was an unwitting initiation into the world of baldness, a style I would come to embrace in later years, long after the Afros of my youth had given way to the simplicity of a shiny bald head.

Then my mother drove me to a photo studio to immortalized the occasion. The photo shop close to the cathedral, was at the intersection of rue des Miracles and rue Monseigneur Guilloux. The place seemed as ancient as photography itself. Its window, adorned with a mosaic of portraits, hinted at the photographer’s versatility and his likely alliance with the Frères for capturing the pivotal moments of First Communion. My mother’s choice to bring me there, over the more renowned Chaton studio, was perhaps not coincidental but a deliberate nod to tradition.

Inside, the photographer’s efficiency was evident. With a bench repurposed as a kneeler, rosary beads delicately arranged atop a small bible, and a steady gaze into the lens, the photographer took his shots! The session was brief yet momentous. These photographs would serve as timeless mementos of a significant spiritual passage at Saint Louis.

Tarzan at Saint Louis

In terms of extra-curricular activities at Saint Louis, there were a few bright moments. Among them was a movie theater, complete with the grandeur of heavy black curtains and the intimacy of a narrow yet elongated space. It was here that we were introduced to the cinematic exploits of Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan. The black and white imagery, the athletic prowess of a crazed white man swinging from tree to tree, and the exotic wildlife captivated us. Every scene with Jane was pure joy! We had never seen elephants, lions and monkeys before, these outings offered a window into a world far removed from our own.

“Haile Sélasié, min Duvalier cé fè!” (Haile is steel but Duvalier is iron!)

Yet, these films also bore the marks of their time, reflecting the prevailing racial attitudes of Hollywood’s past. Every time we saw black people in a scene, they were either porters or portrayed as wild savages with bones running thru their noses. As if that was not enough, they had them speak this incomprehensible, gibberish language as if it was some kind of an African dialect. The portrayal of black characters was a stark reminder of the era’s prejudices, a discordant note in the otherwise enchanting escapades of Tarzan and Jane.

During the show, the ever present Frères stood guard at the very top where they had a bird’s eye view of the entire class. In those days, cinemas were plentiful in Port au Prince and it was a very popular past time in Haiti.

The Lion of Judah in Haiti

A momentous historical event unfolded before us on April 25th, 1966, when Emperor Haile Selassie graced Haiti with his presence. Whether it was a formal invitation from Duvalier or a strategic stopover en route to Jamaica, his visit was a spectacle of grandeur. Duvalier, ever the showman, ensured that the imperial motorcade was a display of opulence, commandeering Mercedes from the affluent to escort the Lion of Judah through the streets of Port-au-Prince.

Dressed to impress, Duvalier donned a formal top hat and coattails, his stature elevated beside the ever-present Manman Simone. I have to say that the Doc looked sharp! His wife wore her habitual wide brimmed hat. If Haitians felt proud that day, the idea really was to mystify the Emperor and remind him that he had landed in Haiti, the world’s epicenter of Voodoo! The newly completed international airport served as a fitting stage for the Emperor’s arrival, adorned with the flags of Haiti and Ethiopia. The red carpet, military regalia, and the iconic black 1953 Mercedes 300 Adenauer limousine underscored the ceremonial grandeur of the occasion.

The Emperor’s diminutive stature was no match for Duvalier’s heightened appearance, thanks to his top hat. The playful Haitian wit coined the phrase “Haile Sélasié, min Duvalier cé fè!” (Haile is steel but Duvalier is iron!), capturing the spirit of the day.

As students, we were gathered at the back entrance, overlooking Grand Rue, to witness the motorcade’s procession to the National Palace. The anticipation was palpable among the throngs of people lining the street. As the cavalcade passed, the air was filled with cheers, the fluttering of flags, and the collective chant of “Haile Sélasié, min Duvalier cé fè!”a unifying cry that resonated with pride and humor.

The Lion of Judah was on Haitian soil for only one day, a fleeting visit to say the least. Emperor Haile Selasie was a wise man as you could never be too sure with the enigmatic Doc! Echoing the timeless sign-off of Walter Cronkite on his CBS Nightly News: “And that’s the way it was on April 25th, 1966.”

Getting out of the dungeon

The true liberation at Saint Louis came not from scholarly pursuits but from the daily release at 4:00 PM. After eight grueling hours imprisoned within academic walls, freedom beckoned. Rue du Centre would burst into life, a vibrant tableau of parents and chauffeurs gathering up the beaten students. It was a moment to exhale, to share laughter and camaraderie, free from the vigilant gaze of the Frères. Pure freedom!

Lining the school’s exit, a brigade of Marchandes offered sweet respite from the day’s rigor. Their wares, a kaleidoscope of treats: Cham-Cham’s sweet corn allure, Tito’s chewy licorice ribbons, Menthe’s refreshing bite, Boule St Lot’s toothsome challenge, and the classic Chicklets gum. Molasses-rich Bonbon Siro beckoned alongside the pistachio purveyors and Machan’n Paté artisans. And who could forget the siren call of the Red Rose Ice Cream cart, its bells heralding cold sweet delight ?

When you were in class and you heard Red Rose’s bells, you just knew the day was ending. By then your mind was on ice cream. The privileged students went for the Eskimo bars, a luxury at 50 cents. My humble choice, the Crème 10, offered a simple, colorful delight. Yet, I have to say it was the Fresco vendors who captured my heart. Their carts were a rainbow of flavors accompanied by a dance of bees around their syrupy treasures. My favorite flavors were: coconut or grenadine syrup, crowned with a sprinkle of pistachios. A mere 30 cents could buy you a slice of heaven! To this day I miss frescos, still seeking the thrill of its chill.

Alas, time marches on, and with it, the disappearance of these cherished icons. The Titos, the Cham-Chams, lost to the annals of time, a lament for the flavors of youth, now but a sweet memory.

Exodus and Exodus: The Haitian Odyssey

In the shadow of Papa Doc’s regime, our family’s journey began on August 7th, 1966. We departed Haiti, bound for the promise of New York aboard a Pan Am Boeing 707. The city that never sleeps hosted us for 21 days before we ventured to Brussels, a brief European interlude on our path to Kinshasa. Once known as Leopold Ville, the capital of what was then Zaire welcomed us with open arms.

My mother, an educator in geography, and my father a civil engineer/mathematician, were to impart knowledge in this new land. Mid-flight, my mother roused me to witness the Sahara’s vast expanse, a sea of sand stretching beyond the horizon. Our reunion with my father at Kinshasa’s airport marked the end of his two-year absence, a poignant moment of familial reconnection.

Awaiting their assignments, my parents lingered in the capital for three weeks. Eventually, both of them were assigned to Mbuji Mayi in the Kasai Oriental, a heartland nestled within a nation quadruple the size of France. There, among 22 Haitian teachers and their kin, we found a community, a diaspora of intellects, victims of François Duvalier’s most heinous act: the initiation of Haiti’s brain drain.

The photograph, a testament to the era, captures 28 Haitian educators embarking for the Congo in 1961. Their departure spoke volumes of Haiti’s educational prowess, so esteemed that the United Nations sought their expertise. Among them, I surmise, were alumni of Saint Louis, Lycée Pétion, Collège Odéide, Centre d’Etudes Secondaires, École Normale, bastions of learning that once illuminated Haiti.

In the present disarray, where the unenlightened wield power, the roots of Haiti’s unraveling trace back to the early sixties, to Duvalier’s reign. His promotion of mediocrity, cloaked as social advancement for the marginalized, was a facade for securing unwavering allegiance. This legacy, a tradition of substandard expectations, has only intensified with time. This can not be overstated: to understand Haiti’s present calamity, It is essential in my humble opinion to revisit the early sixties to grasp the wrongs that Francois Duvalier did to this country!

A New Chapter: From the Heart of Africa to the Halls of New York

As the African sun set on our year-long adventure, my parents, guided by wisdom and foresight, chose a new horizon for us: the United States. The bustling metropolis of New York was to be our new home. My elder brother led the way, departing Congo for Brussels, while two of my siblings ventured to the political heart of the US, Washington DC. By late June of 1967, my younger brother and I bid farewell to Mbuji Mayi, setting our sights on the Big Apple.

Upon arrival, mastering English was paramount, so a tutor was promptly engaged. My father, ever the strategist, enlisted an immigration attorney to navigate the labyrinth of residency paperwork. With legalities settled, the educational odyssey resumed. To my astonishment, I was not done with the Catholic school system. No sir! I found myself enrolled at St. Bartholomew in Elmhurst, New York, under the tutelage of the Franciscan Brothers.

St. Bartholomew I must say was a revelation, a stark contrast to my previous schooling. The Franciscan Brothers fostered a nurturing environment, devoid of fear and punishment. Their compassionate approach and unwavering patience ensured that every lesson resonated deeply. Brother Maurice, in particular, stood out as a beacon of guidance and support.

The school’s principal, Brother George, defied the archetype of the fearsome disciplinarian, instead offering religious instruction that uplifted and inspired. It’s no surprise that my academic performance soared. I thrived, free from the shackles of anxiety and humiliation, and discovered a newfound zeal for learning.

As high school beckoned, I transitioned to the esteemed Newtown H.S., a public institution renowned for its diversity and excellence. There, I reunited with former Saint Louis compatriots, Alix Lamarre and Jean Fabius. Elmhurst had evolved into a microcosm of Port-au-Prince, a testament to the exodus spurred by François Duvalier’s oppressive regime.

My academic journey culminated in triumph, with commendable achievements in high school, junior college in Washington, and ultimately, the prestigious halls of UCLA in California.

Saint Louis Revisited

In the quiet corridors of memory, Saint Louis stands as a complex tapestry, a blend of reverence and frustration. To this day, the Frères, those stern custodians of knowledge, evoke a spectrum of emotions. While I harbor no animosity, their authoritarian ways remain etched in my recollections.

Brother Maurice, a beacon of compassion at St. Bartholomew in New York, stands in stark contrast to the Frères of Saint Louis. His patient guidance and empathy breathed life into learning. Yet, Saint Louis remains a distant echo, its walls echoing both wisdom and absurdity.

The grotesque privilege of the White man’s burden weighed heavily within those hallowed halls. Haiti, a nation that had triumphed over French dominion, deserved better. A Ministry of Education check-and-balance system should have curtailed the excesses. For example, my brother Lionel who attended Saint Louis was initially left handed, they forced him to use his right hand. That practice was pervasive at Saint Louis and it left a good many students with a most unattractive handwriting.

As for corporal punishment, none of what I described should ever have been allowed!

I suppose the legacy of slavery in this country had demolished the self esteem of a good many people to the point of them still being in awe of the pale skinned.

Yet, amidst this turmoil, Saint Louis imparted an education, an odd blend of Latin, Greek, and Solfège. Archaic, perhaps, but it unraveled etymological mysteries, revealing the origins of words. Calligraphy, Orthography, and Grammar wove practical threads into our minds, preparing us for life.

And so, with ink-stained hands and hearts, we emerge products of both grace and strife. Saint Louis, flawed yet formative, remains a chapter in our collective story.

In conclusion, let me say that I have no qualms with the quality of the education which was offered at Saint Louis de Gonzague it is the manner in which it was done!

Amazingly succulent 👍🏽keep it up, great content .

Wonderful entertaining reading my friend!

Thank you for the positive feedback guys! I really appreciate it!

Thank you so much Mario for sharing your memories in such a clear and captivating manner. Your painful years at Saint Louis became pretext to tell a wider and very well told story with an incredible richness of vocabulary; it was a delightful reading.

Please tell us more!

Incredibly well written Mario. What a elegant piece that sheds light on the iconic institution that all Haitians know to be Saint Louis, and a illustrative depiction of the Delatour family that readers have the pleasure of learning about(so many family gems that I’ve found myself reading this over and over again!). Thank you for sharing!

Many thanks Babas! Glad you enjoyed the piece and were able to get a glimpse of what the early sixties was like at Saint Louis under Papa Doc!

Thank you for your support!

Reads like a good book!

Cheers!

Wow Parrain this was a phenomenal and enjoyable read. The anecdotes were thought-provoking and humorous. I had no idea my dad was born left handed, but it makes sense why his writing similar to mine unfortunately looks like chicken scratch haha. This blog post was informative and inspirational! By the way you looked incredibly handsome in your communion portrait, but I empathize with your efforts to avoid the Tèt Kalé Bobis” haircut.